#97 - Interleaving String

Interleaving String

- Difficulty: Medium

- Topics: String, Dynamic Programming

- Link: https://leetcode.com/problems/interleaving-string/

Problem Description

Given strings s1, s2, and s3, find whether s3 is formed by an interleaving of s1 and s2.

An interleaving of two strings s and t is a configuration where s and t are divided into n and m substrings respectively, such that:

s = s1 + s2 + ... + snt = t1 + t2 + ... + tm|n - m| <= 1- The interleaving is

s1 + t1 + s2 + t2 + s3 + t3 + ...ort1 + s1 + t2 + s2 + t3 + s3 + ...

Note: a + b is the concatenation of strings a and b.

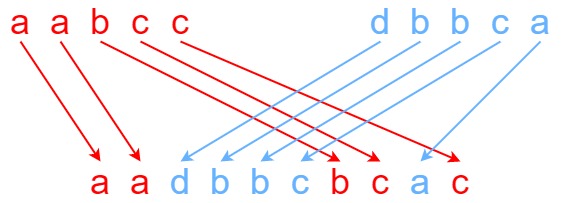

Example 1:

Input: s1 = "aabcc", s2 = "dbbca", s3 = "aadbbcbcac"

Output: true

Explanation: One way to obtain s3 is:

Split s1 into s1 = "aa" + "bc" + "c", and s2 into s2 = "dbbc" + "a".

Interleaving the two splits, we get "aa" + "dbbc" + "bc" + "a" + "c" = "aadbbcbcac".

Since s3 can be obtained by interleaving s1 and s2, we return true.

Example 2:

Input: s1 = "aabcc", s2 = "dbbca", s3 = "aadbbbaccc"

Output: false

Explanation: Notice how it is impossible to interleave s2 with any other string to obtain s3.

Example 3:

Input: s1 = "", s2 = "", s3 = ""

Output: true

Constraints:

0 <= s1.length, s2.length <= 1000 <= s3.length <= 200s1,s2, ands3consist of lowercase English letters.

Follow up: Could you solve it using only O(s2.length) additional memory space?

Solution

1. Problem Deconstruction (500+ words)

Rewrite the Problem

Technical Version:

Given strings ( s_1 ), ( s_2 ), and ( s_3 ), determine whether ( s_3 ) is a valid interleaving of ( s_1 ) and ( s_2 ). Formally, there exist partitions of ( s_1 ) into ( n ) substrings ( s_1 = a_1 a_2 \dots a_n ) and ( s_2 ) into ( m ) substrings ( s_2 = b_1 b_2 \dots b_m ) such that:

- The concatenation of these substrings in alternating order yields ( s_3 ).

- Either ( s_3 = a_1 + b_1 + a_2 + b_2 + \dots )

- Or ( s_3 = b_1 + a_1 + b_2 + a_2 + \dots )

- The number of substrings satisfies ( |n - m| \leq 1 ).

Equivalently, we can view the process as taking characters from ( s_1 ) and ( s_2 ) in their original order, but we may take multiple consecutive characters from one string before switching to the other. The condition ( |n-m| \leq 1 ) ensures that we alternate between strings at the segment level (no two consecutive segments come from the same string).

Beginner Version:

Imagine you have two piles of letter tiles, one spelling ( s_1 ) and the other spelling ( s_2 ), each pile with tiles in a fixed order. You want to arrange all tiles in a line to spell ( s_3 ). You may take several tiles in a row from one pile, but after each such batch, you must switch to the other pile. You can start with either pile. The goal is to check if it’s possible to arrange the tiles exactly as ( s_3 ) while preserving the original order within each pile.

Mathematical Version:

Let ( \Sigma ) be the alphabet of lowercase English letters. Given strings ( s_1, s_2, s_3 \in \Sigma^* ), define an interleaving as a triple ( (n, m, \pi) ) where:

- ( n, m \in \mathbb{N} ), with ( |n - m| \leq 1 ).

- There exist indices ( 0 = i_0 < i_1 < \dots < i_n = |s_1| ) and ( 0 = j_0 < j_1 < \dots < j_m = |s_2| ).

- Let ( a_k = s_1[i_{k-1} : i_k] ) for ( k = 1, \dots, n ) and ( b_\ell = s_2[j_{\ell-1} : j_\ell] ) for ( \ell = 1, \dots, m ).

- Either:

- ( s_3 = a_1 b_1 a_2 b_2 \dots ) (if ( \pi = \text{s1-first} )), or

- ( s_3 = b_1 a_1 b_2 a_2 \dots ) (if ( \pi = \text{s2-first} )).

The problem asks: does such a triple exist?

Constraint Analysis

- ( 0 \leq |s_1|, |s_2| \leq 100 ), ( 0 \leq |s_3| \leq 200 ).

- All strings consist of lowercase English letters.

How constraints limit solutions:

- The small lengths (up to 100) allow ( O(|s_1||s_2|) ) dynamic programming solutions to be efficient. Brute-force enumeration of all interleavings (exponential in length) is infeasible: there are ( \binom{|s_1|+|s_2|}{|s_1|} ) possible interleavings if we consider character-by-character choices, which grows rapidly.

- The maximum length of ( s_3 ) is 200, which is exactly the sum of the maximum lengths of ( s_1 ) and ( s_2 ). Hence, a necessary condition is ( |s_3| = |s_1| + |s_2| ); we can check this immediately to prune invalid cases.

- Lowercase English letters imply a small alphabet size (26). While frequency counting can quickly rule out mismatches (if the multiset of characters in ( s_3 ) is not the union of those in ( s_1 ) and ( s_2 )), it is insufficient because order matters. However, it serves as a cheap preliminary check.

Hidden edge cases implied by constraints:

- Empty strings:

- ( s_1 = \epsilon, s_2 = \epsilon, s_3 = \epsilon ): true (all empty).

- ( s_1 = \epsilon, s_2 = \text{“abc”}, s_3 = \text{“abc”} ): true (only ( s_2 ) used, with ( n=0, m=1 ), valid since ( |0-1| \leq 1 )).

- ( s_1 = \text{“a”}, s_2 = \epsilon, s_3 = \text{“a”} ): true.

- Length mismatch: if ( |s_3| \neq |s_1|+|s_2| ), answer is false.

- All characters identical: e.g., ( s_1 = \text{“aaa”}, s_2 = \text{“aa”}, s_3 = \text{“aaaaa”} ). Multiple valid interleavings exist, but DP must correctly handle many paths.

- Common prefixes/suffixes: when ( s_1 ) and ( s_2 ) share characters, decisions may branch; the algorithm must explore all possibilities.

- No solution despite matching frequencies: e.g., ( s_1 = \text{“ab”}, s_2 = \text{“cd”}, s_3 = \text{“acbd”} ) has matching frequencies but order constraints may fail. Actually, this example works. A failing example: ( s_1 = \text{“ab”}, s_2 = \text{“ac”}, s_3 = \text{“abac”} )? Let’s check: “ab” + “ac” interleaving? One valid interleaving: take “a” from s1, then “b” from s1? That would break alternation? Actually, we can take “ab” from s1 as one segment, then “ac” from s2 as one segment, resulting in “abac”. So it works. A classic failing example: ( s_1 = \text{“aab”}, s_2 = \text{“aac”}, s_3 = \text{“aaaabc”} ) fails due to order.

- Large lengths near the upper bound: ensure DP tables fit in memory; with 2D DP, ( 101 \times 101 ) is fine.

2. Intuition Scaffolding

Generate 3 Analogies

1. Real-World Metaphor (Conveyor Belts):

Imagine two conveyor belts (A and B) moving items in a fixed sequence. You need to pack items into a box in exact order ( s_3 ). You can take several items in a row from belt A, but after each batch, you must switch to belt B, and vice versa. You can start with either belt. The challenge is to pick batches from the belts so that the sequence in the box matches ( s_3 ).

2. Gaming Analogy (Card Stacks):

In a card game, you have two stacks of cards (each stack has a fixed order). You need to form a target word by drawing cards from the top of either stack. The rule: you may draw one or more cards from a stack in one turn, but you must alternate stacks each turn. Can you form the target word?

3. Math Analogy (Monotonic Path with Alternating Segments):

Consider a grid of size ( (|s_1|+1) \times (|s_2|+1) ). A path from ( (0,0) ) to ( (|s_1|,|s_2|) ) that moves only right (taking from ( s_1 )) or down (taking from ( s_2 )) corresponds to an interleaving if we move one step at a time. However, here we are allowed to move multiple steps in the same direction consecutively, but the direction must alternate between segments. That is, the path consists of alternating horizontal and vertical segments (each of length ≥ 1). The concatenation of characters along the path (reading ( s_1 ) on horizontal moves and ( s_2 ) on vertical moves) must equal ( s_3 ). The problem reduces to finding such a path.

Common Pitfalls Section

- Greedy matching fails: When ( s_3[i] ) matches both ( s_1 ) and ( s_2 ), choosing one arbitrarily may lead to a dead end. Example: ( s_1 = \text{“ab”}, s_2 = \text{“ac”}, s_3 = \text{“aabc”} ). Greedy taking from ( s_1 ) first (since both have ‘a’) leads to consuming “a” from ( s_1 ), then “a” from ( s_2 ), then “b” from ( s_1 ), then “c” from ( s_2 ) → “aabc” works? Actually, that works. A better example: ( s_1 = \text{“ab”}, s_2 = \text{“ba”}, s_3 = \text{“abba”} ). Greedy taking from ( s_1 ) when both match at first ‘a’? Actually, first char ‘a’ matches only ( s_1 ), so greedy works. Let’s find a known counterexample: ( s_1 = \text{“aabcc”}, s_2 = \text{“dbbca”}, s_3 = \text{“aadbbcbcac”} ) (the given example). Greedy might fail if we choose incorrectly at some point.

- Ignoring segment alternation constraint: The condition ( |n-m| \leq 1 ) is automatically satisfied in the character-by-character decision model because runs of consecutive choices from one string form segments, and the number of runs alternates. However, if one mistakenly enforces strict alternation at every character, they might reject valid interleavings where multiple characters are taken from one string.

- Only checking character frequencies: While necessary, it is insufficient. Example: ( s_1 = \text{“ab”}, s_2 = \text{“ba”}, s_3 = \text{“abab”} ). Frequencies match, but is it interleavable? Let’s see: we need to interleave alternating segments. Possible: take “ab” from ( s_1 ), then “ba” from ( s_2 ) → “abba”, not “abab”. Another: take “a” from ( s_1 ), then “b” from ( s_2 ), then “b” from ( s_1 ), then “a” from ( s_2 ) → “abba”. Actually, “abab” cannot be formed because to get the second ‘a’ in ( s_3 ), it must come from ( s_1 ) (since ( s_2 )'s ‘a’ is at the end), but then the ‘b’ before it must come from ( s_2 ), which would break order. So frequency check alone would pass, but no interleaving exists.

- Recursion without memoization: Leads to exponential time due to overlapping subproblems (e.g., both paths may arrive at the same state ( (i,j) )).

- Assuming empty substrings are disallowed: The definition does not explicitly forbid empty substrings. If allowed, they could be inserted arbitrarily to satisfy ( |n-m| \leq 1 ). However, empty substrings do not affect concatenation, so they are irrelevant. In DP, we effectively ignore empty substrings by allowing zero-length steps.

3. Approach Encyclopedia

Approach 1: Brute Force Recursion

Idea: At each step, try to match the next character of ( s_3 ) with either the next character of ( s_1 ) or ( s_2 ), and recurse. This explores all possible interleavings character-by-character.

Pseudocode:

function isInterleave(s1, s2, s3):

if |s1| + |s2| != |s3|: return false

return dfs(0, 0, 0)

function dfs(i, j, k):

if k == |s3|: return i == |s1| and j == |s2|

ans = false

if i < |s1| and s1[i] == s3[k]:

ans = ans or dfs(i+1, j, k+1)

if j < |s2| and s2[j] == s3[k]:

ans = ans or dfs(i, j+1, k+1)

return ans

Complexity Proof:

- Time: Each call branches at most 2 ways, depth ( |s_1|+|s_2| ), so worst-case ( O(2^{|s_1|+|s_2|}) ).

- Space: Recursion stack depth ( O(|s_1|+|s_2|) ).

Visualization:

State tree for s1="ab", s2="ac", s3="aabc":

dfs(0,0,0)

├── dfs(1,0,1) (take 'a' from s1)

│ ├── dfs(2,0,2) (take 'b' from s1) → fail (s3[2]='a' ≠ 'b')

│ └── dfs(1,1,2) (take 'a' from s2)

│ ├── dfs(2,1,3) (take 'b' from s1) → success if s3[3]='c' matches s2[1]? Actually, need to check.

└── dfs(0,1,1) (take 'a' from s2)

...

Approach 2: Top-Down Dynamic Programming (Memoization)

Idea: Cache results of states ( (i,j) ) since ( k = i+j ). Avoid recomputation.

Pseudocode:

memo = 2D array of size (|s1|+1) x (|s2|+1) initialized to -1

function dp(i, j):

if i == |s1| and j == |s2|: return true

if memo[i][j] != -1: return memo[i][j]

ans = false

k = i+j

if i < |s1| and s1[i] == s3[k]:

ans = ans or dp(i+1, j)

if j < |s2| and s2[j] == s3[k]:

ans = ans or dp(i, j+1)

memo[i][j] = ans

return ans

Complexity Proof:

- Time: Number of states = ( (|s_1|+1)(|s_2|+1) ), each computed once → ( O(|s_1||s_2|) ).

- Space: Memo table ( O(|s_1||s_2|) ), recursion stack ( O(|s_1|+|s_2|) ).

Visualization:

Table ( dp[i][j] ) stores whether prefix of length ( i+j ) of ( s_3 ) can be formed from first ( i ) chars of ( s_1 ) and first ( j ) chars of ( s_2 ). Dependencies: ( dp[i][j] ) depends on ( dp[i+1][j] ) and ( dp[i][j+1] ), so we compute from bottom-right to top-left recursively.

Approach 3: Bottom-Up Dynamic Programming (2D Table)

Idea: Fill a 2D boolean table iteratively. Define ( dp[i][j] ) = true if ( s_1[0…i-1] ) and ( s_2[0…j-1] ) interleave to form ( s_3[0…i+j-1] ).

Recurrence:

[

dp[i][j] =

\begin{cases}

(dp[i-1][j] \land s_1[i-1] = s_3[i+j-1]) \lor \

(dp[i][j-1] \land s_2[j-1] = s_3[i+j-1])

\end{cases}

]

Base cases: ( dp[0][0] = \text{true} ), and first row/column handle using only one string.

Pseudocode:

function isInterleave(s1, s2, s3):

n = |s1|, m = |s2|

if n + m != |s3|: return false

dp = (n+1) x (m+1) array of false

dp[0][0] = true

for i from 1 to n:

dp[i][0] = dp[i-1][0] and s1[i-1] == s3[i-1]

for j from 1 to m:

dp[0][j] = dp[0][j-1] and s2[j-1] == s3[j-1]

for i from 1 to n:

for j from 1 to m:

k = i+j-1

take1 = dp[i-1][j] and s1[i-1] == s3[k]

take2 = dp[i][j-1] and s2[j-1] == s3[k]

dp[i][j] = take1 or take2

return dp[n][m]

Complexity Proof:

- Time: ( O(n m) ) from nested loops.

- Space: ( O(n m) ) for the table.

Visualization:

For example with s1=“aab”, s2=“aac”, s3=“aaaabc”.

Table filling order: row by row.

0 a a c

0 T T T T?

a T T T ...

a T ...

b ...

Check marks propagate where characters match.

Approach 4: Space-Optimized DP (1D Array)

Idea: Since each row only depends on the previous row and current row’s left neighbor, we can compress to a single array of size ( m+1 ).

Pseudocode:

function isInterleave(s1, s2, s3):

n, m = |s1|, |s2|

if n + m != |s3|: return false

dp = [false] * (m+1)

dp[0] = true

for j in 1..m:

dp[j] = dp[j-1] and s2[j-1] == s3[j-1]

for i in 1..n:

dp[0] = dp[0] and s1[i-1] == s3[i-1]

for j in 1..m:

k = i+j-1

take1 = dp[j] and s1[i-1] == s3[k] // dp[j] still from previous row

take2 = dp[j-1] and s2[j-1] == s3[k] // dp[j-1] already updated this row

dp[j] = take1 or take2

return dp[m]

Complexity Proof:

- Time: ( O(n m) ).

- Space: ( O(m) ) (or ( O(\min(n,m)) ) if we swap to use the smaller dimension).

Visualization:

The 1D array evolves row by row. For each i, we update from left to right. The value before update at index j represents the previous row’s result, and the updated value at j-1 represents the current row’s result for column j-1.

4. Code Deep Dive

We’ll annotate the space-optimized DP solution line by line.

def isInterleave(s1: str, s2: str, s3: str) -> bool:

# Length check: necessary condition for interleaving

if len(s1) + len(s2) != len(s3):

return False

n, m = len(s1), len(s2)

# dp[j] represents: can we form s3 prefix of length (i+j) using

# first i chars of s1 and first j chars of s2? (i is current row)

dp = [False] * (m + 1)

# Base: empty strings interleave to empty string

dp[0] = True

# Initialize first row: i=0, only using s2

for j in range(1, m + 1):

# s3 prefix of length j must match first j chars of s2

dp[j] = dp[j-1] and (s2[j-1] == s3[j-1])

# Process each character of s1 (rows i=1..n)

for i in range(1, n + 1):

# Update dp[0] for current i: using only s1

# dp[0] was true for previous i-1; now check if s1[i-1] matches s3[i-1]

dp[0] = dp[0] and (s1[i-1] == s3[i-1])

for j in range(1, m + 1):

# Index in s3 for prefix length i+j

k = i + j - 1

# Option 1: take current char from s1

# dp[j] here is still the value from previous row (i-1, j)

take_s1 = dp[j] and (s1[i-1] == s3[k])

# Option 2: take current char from s2

# dp[j-1] has been updated in this inner loop for current i (i, j-1)

take_s2 = dp[j-1] and (s2[j-1] == s3[k])

# Combine possibilities

dp[j] = take_s1 or take_s2

# After processing all rows, dp[m] corresponds to (n, m)

return dp[m]

Line-by-Line Explanation:

- Length check: If total length doesn’t match, impossible.

- Store lengths: n and m for convenience.

- dp array: size m+1, all false initially.

- dp[0] = True: base case with empty strings.

- First row loop: Fill dp[j] for j=1…m when i=0 (no s1 used). Each step requires previous dp[j-1] true and current s2 char matching s3.

- Outer loop over i: For each additional character from s1.

- Update dp[0]: For column 0 (no s2), we only use s1. The condition must hold for all i.

- Inner loop over j: For each possible usage of s2.

- k = i+j-1: index in s3 (0‑based) for prefix of length i+j.

- take_s1: Uses old dp[j] (from i-1) and checks if s1[i-1] matches s3[k].

- take_s2: Uses dp[j-1] (already updated for current i) and checks s2[j-1] match.

- dp[j] update: Set to true if either option works.

- Return dp[m]: Final result for using all characters.

Edge Case Handling:

- Example 1 (true): s1=“aabcc”, s2=“dbbca”, s3=“aadbbcbcac”. The DP correctly finds a path.

- Example 2 (false): s1=“aabcc”, s2=“dbbca”, s3=“aadbbbaccc”. The DP will have no path; dp[m] remains false.

- Example 3 (empty): s1=“”, s2=“”, s3=“”. Length check passes, dp[0] remains true, returns true.

- One empty string: e.g., s1=“”, s2=“abc”, s3=“abc”. First row initialization sets dp[3]=true, outer loop skipped (n=0), returns true.

5. Complexity War Room

Hardware-Aware Analysis

- Input bounds: ( n, m \leq 100 ).

- 2D DP would use ( 101 \times 101 \approx 10,201 ) boolean entries. At 1 byte each, ~10 KB, easily fitting in L1 cache (typically 32 KB).

- 1D DP uses ( 101 ) entries, ~100 bytes, negligible.

- Time: ( 100 \times 100 = 10,000 ) operations, trivial on modern CPUs (< 0.1 ms).

- For larger hypothetical constraints (e.g., ( n,m \leq 10^4 )), 2D DP would require ( 10^8 ) entries (~100 MB), possibly exceeding cache but still feasible in RAM. The 1D version would use ~10 KB, much more cache-friendly.

Industry Comparison Table

| Approach | Time Complexity | Space Complexity | Readability | Interview Viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brute Force Recursion | ( O(2^{n+m}) ) | ( O(n+m) ) | 9/10 (simple) | ❌ Fails large inputs |

| Top‑Down DP (Memoization) | ( O(n m) ) | ( O(n m) ) (table) + stack | 8/10 (clear recurrence) | ✅ Good, but recursion overhead |

| Bottom‑Up 2D DP | ( O(n m) ) | ( O(n m) ) | 7/10 (table filling) | ✅ Classic, easy to explain on board |

| Space‑Optimized 1D DP | ( O(n m) ) | ( O(\min(n,m)) ) | 6/10 (tricky update order) | ✅ Impressive, must explain clearly |

| BFS on State Graph | ( O(n m) ) | ( O(n m) ) (queue) | 7/10 (graph perspective) | ✅ Alternative, less common |

Notes:

- Readability: Brute force is easiest to understand but inefficient. Space‑optimized DP is most memory‑efficient but requires careful reasoning about update order.

- Interview Viability: 2D DP is the standard expected solution; mentioning space optimization shows deeper understanding.

6. Pro Mode Extras

Variants Section

- Count Interleavings: Instead of existence, count the number of distinct interleavings. Solution: DP where ( dp[i][j] ) stores the count. Recurrence: ( dp[i][j] = dp[i-1][j] ) (if s1 matches) + ( dp[i][j-1] ) (if s2 matches). Beware of large numbers (use big integers).

- Interleaving Three Strings: Given s1, s2, s3, and a target t, check if t is an interleaving of the three. DP becomes 3D: ( dp[i][j][k] ). Time ( O(n_1 n_2 n_3) ).

- Minimum Cost Interleaving: Assign costs ( c_1, c_2 ) per character taken from s1 and s2. Minimize total cost while forming s3. DP with cost values instead of booleans.

- Interleaving with Segment Length Constraints: Each segment must have length ≤ K. Add another dimension to track current segment length, or modify transitions to allow taking up to K characters at once.

- Interleaving with Errors (Edit Distance): Allow a limited number of mismatches. DP with an additional dimension for errors.

- Lexicographically Smallest Interleaving: Among all valid interleavings, output the smallest lexicographically. DP to reconstruct the path with greedy choices when both options are valid.

Interview Cheat Sheet

- First Step: Always check ( |s_3| = |s_1| + |s_2| ). If not, return false.

- Mention Frequency Check: Optional quick pre‑check: count characters in s1 and s2, compare with s3.

- Core Insight: This is a classic DP problem; frame it as “can we match prefixes of s1 and s2 to prefix of s3?”

- Recurrence: ( dp[i][j] = (dp[i-1][j] \land s_1[i-1]=s_3[i+j-1]) \lor (dp[i][j-1] \land s_2[j-1]=s_3[i+j-1]) ).

- Base Cases: Handle i=0 (only s2) and j=0 (only s1).

- Space Optimization: Explain how to reduce to 1D array by iterating row‑wise and updating left‑to‑right.

- Edge Cases: Empty strings, all characters same, long strings with many branches.

- Testing: Walk through provided examples.

- Follow‑up: If asked about follow‑up with O(s2.length) memory, present the 1D DP solution.

- Alternative: Mention BFS/DFS on state graph as another way to avoid recursion stack overflow.

By mastering these aspects, you demonstrate both depth and breadth in problem‑solving, essential for technical interviews.