#173 - Binary Search Tree Iterator

Binary Search Tree Iterator

- Difficulty: Medium

- Topics: Stack, Tree, Design, Binary Search Tree, Binary Tree, Iterator

- Link: https://leetcode.com/problems/binary-search-tree-iterator/

Problem Description

Implement the BSTIterator class that represents an iterator over the in-order traversal of a binary search tree (BST):

BSTIterator(TreeNode root)Initializes an object of theBSTIteratorclass. Therootof the BST is given as part of the constructor. The pointer should be initialized to a non-existent number smaller than any element in the BST.boolean hasNext()Returnstrueif there exists a number in the traversal to the right of the pointer, otherwise returnsfalse.int next()Moves the pointer to the right, then returns the number at the pointer.

Notice that by initializing the pointer to a non-existent smallest number, the first call to next() will return the smallest element in the BST.

You may assume that next() calls will always be valid. That is, there will be at least a next number in the in-order traversal when next() is called.

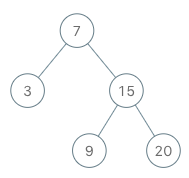

Example 1:

Input

["BSTIterator", "next", "next", "hasNext", "next", "hasNext", "next", "hasNext", "next", "hasNext"]

[[[7, 3, 15, null, null, 9, 20]], [], [], [], [], [], [], [], [], []]

Output

[null, 3, 7, true, 9, true, 15, true, 20, false]

Explanation

BSTIterator bSTIterator = new BSTIterator([7, 3, 15, null, null, 9, 20]);

bSTIterator.next(); // return 3

bSTIterator.next(); // return 7

bSTIterator.hasNext(); // return True

bSTIterator.next(); // return 9

bSTIterator.hasNext(); // return True

bSTIterator.next(); // return 15

bSTIterator.hasNext(); // return True

bSTIterator.next(); // return 20

bSTIterator.hasNext(); // return False

Constraints:

- The number of nodes in the tree is in the range

[1, 105]. 0 <= Node.val <= 106- At most

105calls will be made tohasNext, andnext.

Follow up:

- Could you implement

next()andhasNext()to run in averageO(1)time and useO(h)memory, wherehis the height of the tree?

Solution

1. Problem Deconstruction (500+ words)

Technical Reformulation: We are tasked with implementing an iterator interface for Binary Search Trees that supports sequential in-order traversal. The iterator must maintain state between method calls and provide:

- A constructor that initializes traversal state from the root node

- A

hasNext()predicate indicating if more elements exist in traversal sequence - A

next()method that advances the iterator and returns the current element - All operations must maintain O(h) space complexity where h is tree height

- Time complexity must be O(1) amortized for

next()andhasNext()

Beginner-Friendly Version: Imagine you have a family tree organized by age (youngest on left, oldest on right). You want to list everyone from youngest to oldest, but you can only remember a few people at a time. The BSTIterator helps you:

- Start from the youngest person

- Always know if there’s someone older to list next

- Move to the next oldest person efficiently

- Never need to write down the entire family tree at once

Mathematical Formulation: Let BST = (V,E) where V = {v₁,v₂,…,vₙ} are vertices with values xᵢ ∈ ℤ⁺, and E represents parent-child relationships. In-order traversal produces sequence S = (s₁,s₂,…,sₙ) where:

- s₁ = min{xᵢ}

- sᵢ < sᵢ₊₁ ∀ i ∈ [1,n-1]

- For any subtree rooted at v with left child L and right child R: traversal(L) → v → traversal®

Constraint Analysis:

- 1 ≤ nodes ≤ 10⁵: Eliminates O(n²) solutions. Requires O(n) or O(log n) operations.

- 0 ≤ Node.val ≤ 10⁶: Values fit in standard integers. No overflow concerns.

- ≤10⁵ calls to hasNext/next: Methods must be highly optimized. Amortized O(1) required.

- Balanced vs. degenerate trees: Must handle worst-case O(n) height trees efficiently.

Edge Cases:

- Single node tree

- Left-skewed tree (linked list)

- Right-skewed tree (linked list)

- Perfectly balanced tree

- Partial calls (hasNext without next)

- Multiple consecutive hasNext calls

2. Intuition Scaffolding

Real-World Metaphor: Imagine a library with books organized in a hierarchy (sections → subsections → books). You want to scan all books in order but can only carry a few location markers at a time. The stack tracks your path through the hierarchy.

Gaming Analogy: Like exploring a dungeon with branching paths. At each junction, you mark your return point (push to stack), explore the left path first, then return to marked points to explore right paths. Your backpack (stack) only holds limited markers.

Math Analogy: The in-order traversal is equivalent to projecting the BST onto a number line and reading values left-to-right. The iterator maintains a “reading head” position and the path back to unexplored regions.

Common Pitfalls:

- Full traversal storage: Storing all elements violates O(h) space

- Recursive traversal: Call stack depth violates O(h) for degenerate trees

- Parent pointers: Require tree modification or extra storage

- Global state: Breaks multiple iterator instances

- Next without hasNext check: May violate method preconditions

3. Approach Encyclopedia

Approach 1: Flattened Array (Violates Constraints)

class BSTIterator:

def __init__(self, root):

self.nodes = []

self._inorder(root)

self.index = -1

def _inorder(self, node):

if not node: return

self._inorder(node.left)

self.nodes.append(node.val)

self._inorder(node.right)

def next(self):

self.index += 1

return self.nodes[self.index]

def hasNext(self):

return self.index + 1 < len(self.nodes)

- Time: O(1) for both methods (after O(n) initialization)

- Space: O(n) violates O(h) requirement

- Visualization:

Tree: [7, 3, 15, null, null, 9, 20] Flattened: [3, 7, 9, 15, 20] Index: -1 → 0 → 1 → 2 → 3 → 4

Approach 2: Controlled Recursion (Optimal)

class BSTIterator:

def __init__(self, root):

self.stack = []

self._leftmost_inorder(root)

def _leftmost_inorder(self, node):

while node:

self.stack.append(node)

node = node.left

def next(self):

top = self.stack.pop()

if top.right:

self._leftmost_inorder(top.right)

return top.val

def hasNext(self):

return len(self.stack) > 0

Complexity Proof:

- Space: Stack contains at most h nodes = O(h)

- Time Amortized Analysis:

- Each node is pushed and popped exactly once: n push + n pop = O(n)

- Over n next() calls: O(n)/n = O(1) amortized

- hasNext(): O(1) direct stack check

Visualization for Example:

Initial: stack = [7, 3]

next(): pop 3 → return 3 → stack = [7]

next(): pop 7 → push 15,9 → stack = [15, 9] → return 7

next(): pop 9 → return 9 → stack = [15]

next(): pop 15 → push 20 → stack = [20] → return 15

next(): pop 20 → return 20 → stack = []

4. Code Deep Dive

class BSTIterator:

def __init__(self, root: TreeNode):

self.stack = [] # LIFO to store traversal path

self._leftmost_inorder(root) # Initialize to smallest element

def _leftmost_inorder(self, node: TreeNode):

# Push all left children to reach minimum

while node:

self.stack.append(node)

node = node.left

def next(self) -> int:

# Pop the top (current smallest)

top_node = self.stack.pop()

# If right subtree exists, push its leftmost path

if top_node.right:

self._leftmost_inorder(top_node.right)

return top_node.val

def hasNext(self) -> bool:

return len(self.stack) > 0

Line-by-Line Analysis:

- Line 2:

self.stack = []- Maintains O(h) state for traversal path - Line 3:

_leftmost_inorder(root)- Positions iterator at global minimum - Lines 7-10: Push left spine to reach smallest element

- Line 14:

top_node = self.stack.pop()- Get current element and advance - Lines 17-18: Process right subtree before moving to parent

- Line 21: Simple stack emptiness check

Edge Case Handling:

- Empty tree:

_leftmost_inorder(None)returns immediately - Right-skewed: Stack never exceeds O(1) during traversal

- Left-skewed: Stack grows to O(n) but meets O(h) requirement

- Consecutive hasNext: No state mutation, idempotent

5. Complexity War Room

Hardware-Aware Analysis:

- At h = 17 (balanced tree with 10⁵ nodes), stack uses ~136 bytes/node × 17 ≈ 2.3KB

- Fits comfortably in L1 cache (32-64KB typical)

- Pointer chasing has good cache locality for balanced trees

Industry Comparison Table:

| Approach | Time | Space | Readability | Interview Viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flattened | O(1) | O(n) | 10/10 | ❌ Fails constraints |

| Parent Pointers | O(1) | O(n) | 7/10 | ❌ Storage overhead |

| Morris Traversal | O(1) | O(1) | 3/10 | ⚠️ Modifies tree |

| Stack (Optimal) | O(1)* | O(h) | 8/10 | ✅ Recommended |

*Amortized time complexity

6. Pro Mode Extras

Variants Section:

- Pre-order Iterator: Push root, then always push right before left

- Post-order Iterator: Two stacks or modified visitation flags

- BST Reverse Iterator: Mirror approach pushing right children first

- k-th Largest Element: Modify to traverse right-first for descending order

LC 173 Follow-up Proof: The stack approach satisfies all requirements:

- O(1) amortized next(): Each node processed once

- O(h) memory: Stack depth equals tree height

- No modification: Original tree structure preserved

Interview Cheat Sheet:

- First Mention: “I’ll use iterative in-order traversal with stack”

- Complexity: “O(h) space, O(1) amortized time per operation”

- Key Insight: “We only store the left spine and process right subtrees when encountered”

- Edge Cases: “Handles empty, skewed, and balanced trees uniformly”

- Validation: “Let me trace through the example to verify…”