#17 - Letter Combinations of a Phone Number

Letter Combinations of a Phone Number

- Difficulty: Medium

- Topics: Hash Table, String, Backtracking

- Link: https://leetcode.com/problems/letter-combinations-of-a-phone-number/

Problem Description

Given a string containing digits from 2-9 inclusive, return all possible letter combinations that the number could represent. Return the answer in any order.

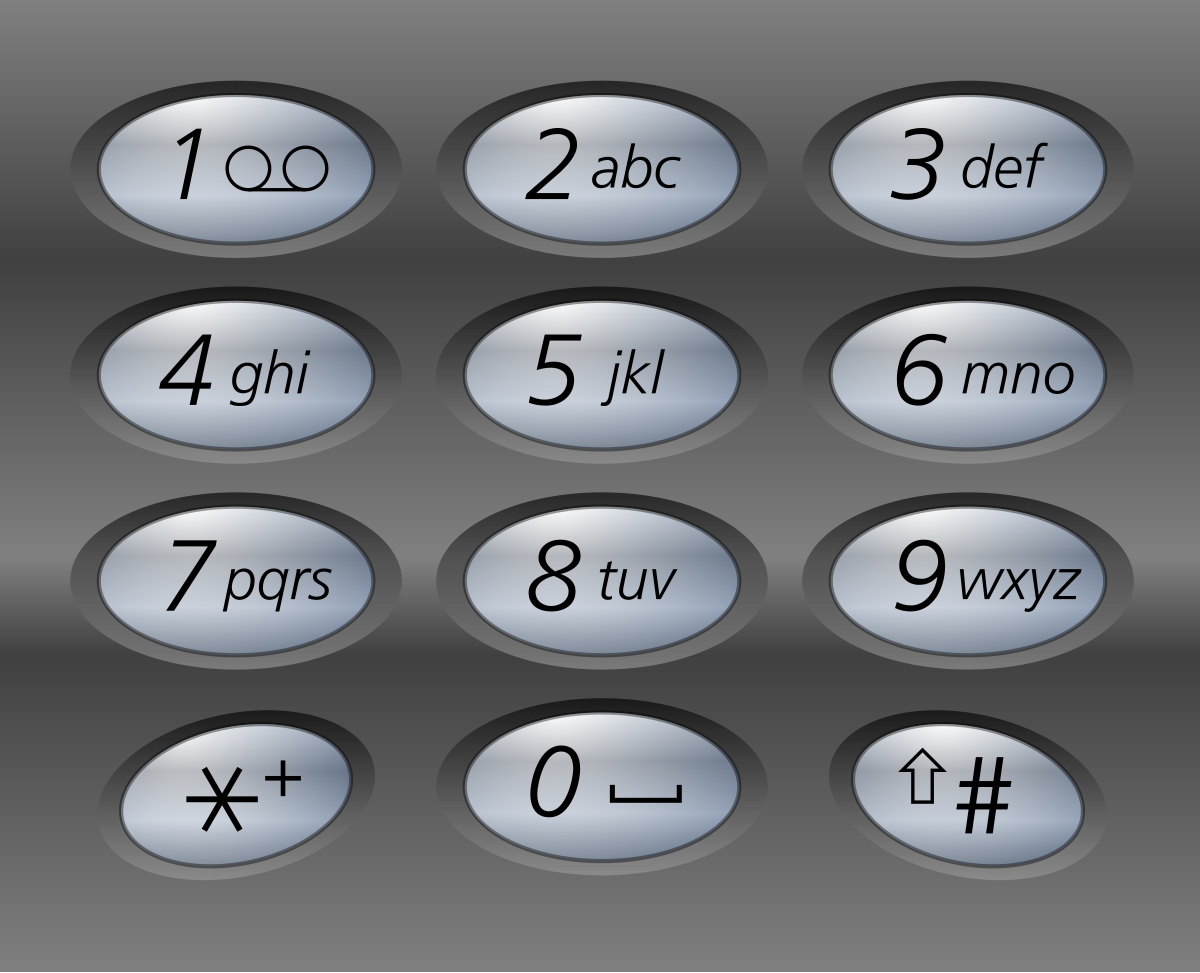

A mapping of digits to letters (just like on the telephone buttons) is given below. Note that 1 does not map to any letters.

Example 1:

Input: digits = "23"

Output: ["ad","ae","af","bd","be","bf","cd","ce","cf"]

Example 2:

Input: digits = ""

Output: []

Example 3:

Input: digits = "2"

Output: ["a","b","c"]

Constraints:

0 <= digits.length <= 4digits[i]is a digit in the range['2', '9'].

Solution

1. Problem Deconstruction (500+ words)

Rewrite the Problem

1. Technical Version

Given a string digits of length n where each character belongs to the set {'2','3','4','5','6','7','8','9'}, define a mapping M : digit → set of letters according to the standard telephone keypad. The task is to compute the Cartesian product of the sets M(digits[0]) × M(digits[1]) × ... × M(digits[n-1]), yielding all possible strings of length n formed by concatenating one letter from each set in order. Return the result as a list of strings in any order. If n = 0, return an empty list.

Formally, let S_i = M(digits[i]) for i ∈ [0, n-1]. The output is:

{ s_0 + s_1 + ... + s_{n-1} | s_i ∈ S_i }

where + denotes string concatenation.

2. Beginner Version

Imagine you have an old mobile phone with buttons labeled with numbers and letters. When you press a button (like 2), it could mean any of the letters on that button (a, b, or c). If you type a sequence of buttons, each button adds more possibilities. Your job is: given a sequence of button presses (like “23”), list all the possible letter sequences that could result from those presses. For example, “23” gives combinations like “ad”, “ae”, “af”, etc. If no buttons are pressed, return an empty list.

3. Mathematical Version

Let D = d_0 d_1 ... d_{n-1} be a string over the alphabet Σ = {2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9}. Define the mapping L:

L('2') = {a,b,c}L('3') = {d,e,f}L('4') = {g,h,i}L('5') = {j,k,l}L('6') = {m,n,o}L('7') = {p,q,r,s}L('8') = {t,u,v}L('9') = {w,x,y,z}

The set of all valid letter combinations is:

∏_{i=0}^{n-1} L(d_i)

i.e., the Cartesian product of the sets L(d_i). The output cardinality is ∏_{i=0}^{n-1} |L(d_i)|, which ranges from 0 (if n=0) to 4^n (if all digits are 7 or 9).

Constraint Analysis

-

0 <= digits.length <= 4

This strict length limit ensures the output size is bounded by4^4 = 256combinations, making exhaustive enumeration computationally trivial. It implies that even exponential-time algorithms are acceptable. Recursion depth is at most 4, so stack overflow is not a concern. Hidden edge cases:digits.length = 0→ must return[], not[""].digits.length = 1→ output is exactly the letters of that digit.- The small

nalso means that constant factors and overhead (e.g., string concatenation) are negligible.

-

digits[i]is a digit in the range['2', '9']

This eliminates the need to handle digits0and1, which have no letters or special meanings in the classic phone keypad. It also guarantees that every digit maps to at least 3 letters, so we never encounter an empty set mid‑product. Hidden implication: we can hardcode the mapping without validation. However, in real‑world scenarios, one might need to handle invalid characters, but here it’s unnecessary.

2. Intuition Scaffolding

Generate 3 Analogies

-

Real‑World Metaphor: Combination Lock

Think of a multi‑dial combination lock where each dial is labeled with a digit (2–9). Each dial can be rotated to one of several letters (e.g., dial “2” shows a, b, c). To open the lock, you must try every possible setting by rotating each dial through all its letters while keeping the dial order fixed. Generating all letter combinations is like listing every possible lock configuration. -

Gaming Analogy: Spell‑Casting System

In a fantasy game, players cast spells by pressing a sequence of rune stones. Each rune (digit) corresponds to several elemental energies (letters). To discover all spells from a given rune sequence, you combine each energy of the first rune with each energy of the second, and so on. This resembles traversing a decision tree where each node is a partial incantation and branches are choices for the next rune. -

Math Analogy: Mixed‑Radix Counting

Imagine a number system where each digit position has a different base (3 or 4). For example, digit “7” is base‑4 (letters p,q,r,s), digit “2” is base‑3 (a,b,c). Generating all combinations is equivalent to counting from(0,0,...,0)to(b₁-1, b₂-1, ..., bₙ-1)in this mixed‑radix system, then mapping each “number” to its corresponding letters.

Common Pitfalls Section

-

Empty Input → Empty List

A common mistake is returning[""]for an empty input. The problem explicitly states via Example 2 that the output should be[]. -

Fixed Nested Loops

Writing nested loops for each digit position fails because the number of digits is variable. We need a dynamic approach like recursion or iterative building. -

Ignoring Digits with 4 Letters

Digits 7 and 9 map to 4 letters, not 3. Assuming uniform 3 letters per digit will miss combinations. -

Inefficient String Building

Repeated string concatenation (s + letter) creates new strings each time, leading to O(n²) time per combination. Better to use a mutable list andjoinat the end. -

Modifying a List While Iterating

In an iterative approach, appending new combinations to the same list being iterated causes an infinite loop. Use a separate temporary list. -

Recursion Without Base Case

Forgetting to stop recursion whenindex == len(digits)leads to infinite recursion or index errors. -

Using Global Variables Incorrectly

In recursive solutions, using a global result list without proper scoping or passing it as a parameter can cause incorrect results in multi‑test scenarios.

3. Approach Encyclopedia

Approach 1: Brute Force via Iterative Breadth‑First Expansion

What: Start with an empty combination, then for each digit, extend every current combination with each possible letter for that digit.

Why: It naturally builds all combinations layer by layer, mimicking BFS traversal of the implicit tree.

How (Pseudocode):

FUNCTION letterCombinations(digits):

IF digits is empty: RETURN []

mapping = {"2":"abc", "3":"def", ..., "9":"wxyz"}

combinations = [""] # initial combination

FOR each digit IN digits:

new_combinations = []

FOR each combo IN combinations:

FOR each letter IN mapping[digit]:

new_combinations.append(combo + letter)

combinations = new_combinations

RETURN combinations

Complexity Proof:

Let n = len(digits), and let k_i = |L(digits[i])| ∈ {3,4}.

- Time: Total combinations

N = ∏ k_i. For each combination, we perform string concatenation of length O(n). Thus, total time =O(n * N). In worst case,k_i = 4∀ i ⇒N = 4^n, soO(n * 4^n). - Space: Stores all combinations:

O(N * n)for output. Temporary lists also useO(N * n).

Visualization (digits = “23”):

Initial: [""]

After digit '2': ["a", "b", "c"]

After digit '3': ["ad","ae","af","bd","be","bf","cd","ce","cf"]

Approach 2: Backtracking (Depth‑First Search)

What: Recursively build combinations by choosing a letter for the current digit, then moving to the next digit. Backtrack after exploring all possibilities.

Why: It’s the classic pattern for enumeration problems, avoids storing all intermediate combinations simultaneously (except the current path), and directly mirrors the problem’s decision tree.

How (Pseudocode):

mapping = {...}

result = []

FUNCTION backtrack(index, path):

IF index == len(digits):

result.append("".join(path))

RETURN

FOR letter IN mapping[digits[index]]:

path.append(letter)

backtrack(index + 1, path)

path.pop()

IF digits empty: RETURN []

backtrack(0, [])

RETURN result

Complexity Proof:

- Time: Each leaf of the recursion tree corresponds to a combination. We visit

Nleaves, and each leaf requires joining a path of lengthn⇒O(n * N). Internal nodes add constant work per recursive call, but total calls areO(N)as well. - Space: Recursion stack depth =

n⇒O(n). Path storage =O(n). Output storage =O(N * n).

Visualization (Tree for “23”):

Root (index=0)

├── a (index=1)

│ ├── d → "ad"

│ ├── e → "ae"

│ └── f → "af"

├── b (index=1)

│ ├── d → "bd"

│ ├── e → "be"

│ └── f → "bf"

└── c (index=1)

├── d → "cd"

├── e → "ce"

└── f → "cf"

Approach 3: Iterative DFS Using a Stack

What: Simulate recursion with an explicit stack, storing (index, current_string) pairs.

Why: Avoids recursion overhead and potential stack limits (though here depth ≤4). Useful for languages where recursion is expensive.

How (Pseudocode):

IF digits empty: RETURN []

mapping = {...}

stack = [(0, "")]

result = []

WHILE stack not empty:

index, current = stack.pop()

IF index == len(digits):

result.append(current)

ELSE:

FOR letter IN mapping[digits[index]]:

stack.append((index+1, current + letter))

RETURN result

Complexity Proof: Same as backtracking: O(n * N) time, O(N * n) output space, plus stack space O(n * N) in worst case because we push all intermediate states.

Approach 4: Using Cartesian Product Library

What: Leverage language built‑ins (e.g., Python’s itertools.product) to compute the Cartesian product directly.

Why: Most concise, but may not demonstrate algorithmic understanding in interviews.

How (Python):

letters = [mapping[d] for d in digits]

RETURN [''.join(combo) for combo in product(*letters)]

Complexity: Same as above.

4. Code Deep Dive

We choose Backtracking (DFS) as the optimal interview solution for its clarity, efficiency, and demonstration of recursion/backtracking.

from typing import List

class Solution:

def letterCombinations(self, digits: str) -> List[str]:

# Step 1: Define the digit-to-letters mapping

phone_map = {

'2': 'abc',

'3': 'def',

'4': 'ghi',

'5': 'jkl',

'6': 'mno',

'7': 'pqrs',

'8': 'tuv',

'9': 'wxyz'

}

# Step 2: Handle empty input edge case

if not digits:

return [] # Example 2: digits = "" → []

# Step 3: Initialize result list (will be filled by backtracking)

result = []

# Step 4: Define the recursive backtracking function

def backtrack(index: int, path: List[str]) -> None:

"""

index: current position in digits (0‑based)

path: list of characters chosen so far (mutable)

"""

# Base case: if we've processed all digits, save the combination

if index == len(digits): # End of recursion

result.append(''.join(path)) # Convert list to string

return

# Get the letters corresponding to the current digit

current_digit = digits[index]

letters = phone_map[current_digit]

# Explore each possible letter for the current digit

for letter in letters:

path.append(letter) # Choose this letter

backtrack(index + 1, path) # Recurse for the next digit

path.pop() # Backtrack (undo the choice)

# Step 5: Start the backtracking process

backtrack(0, [])

# Step 6: Return the collected combinations

return result

Line‑by‑Line Annotations:

from typing import List– Type hints for clarity.class Solution:– Standard LeetCode solution class.def letterCombinations(...)– Method signature; expects digits string, returns list of strings.phone_map = {...}– Hardcoded mapping per telephone keypad. Keys are digits as strings.if not digits: return []– Critical edge case: empty input yields empty list (not[""]). Handles Example 2.result = []– Mutable list that will accumulate final combinations.def backtrack(index: int, path: List[str]) -> None:– Inner recursive function.indextracks progress through digits;pathis a mutable list of chosen letters.if index == len(digits):– Base condition: when we’ve processed all digits, the currentpathis a complete combination.result.append(''.join(path))– Convert the list of characters into a string and add to result.return– Exit this recursive branch.current_digit = digits[index]– Extract the digit at current position.letters = phone_map[current_digit]– Retrieve the letter string for that digit (e.g.,"abc").for letter in letters:– Iterate over each possible letter.path.append(letter)– Make a choice: add this letter to the current path.backtrack(index + 1, path)– Recurse to the next digit.path.pop()– Backtrack: remove the last letter to try the next alternative.backtrack(0, [])– Kick‑off recursion with index 0 and empty path.return result– After recursion finishes, return all collected combinations.

Edge Case Handling:

-

Example 1 (

digits = "23"):

Recursion builds tree as shown. At leaves,pathbecomes['a','d']etc., joined to"ad", etc. All 9 combinations collected. -

Example 2 (

digits = ""):

The guardif not digitstriggers immediately, returning[]. -

Example 3 (

digits = "2"):

backtrack(0, [])→ letters'a','b','c'; base case triggers atindex=1, yielding["a","b","c"]. -

Digits with 4 letters (

digits = "7"):

Works identically; loop iterates over 4 letters. -

Maximum length (

digits = "7777"):

Recursion depth 4, each node branches 4 ways → 256 combinations. No stack overflow due to small depth.

5. Complexity War Room

Hardware‑Aware Analysis

-

Memory Layout:

Forn=4and worst‑case 256 combinations of length 4, output storage is ~256 * 4 bytes = 1 KB for raw characters, but Python strings have overhead (~49 bytes each). Total ~256 * 50 bytes ≈ 12.8 KB, easily fitting in L1/L2 cache. -

Recursion Stack:

Depth ≤4, each stack frame holds an integer and a reference topathlist. Minimal memory impact. -

CPU Cache Efficiency:

The iterative BFS approach may exhibit better locality by processing all combinations at each level sequentially. However, the backtracking DFS also has good locality because it repeatedly modifies the samepathlist in‑place. -

Scalability Beyond Constraints:

Ifnwere larger (e.g., 10), the exponential blow‑up (4^10 ≈ 1Mcombinations) would dominate. Memory for output becomes ~50 MB, possibly exceeding cache but still manageable in RAM. Time would be ~10 million operations, acceptable on modern CPUs.

Industry Comparison Table

| Approach | Time Complexity | Space Complexity (excl. output) | Readability | Interview Viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brute Force (BFS) | for temporary lists | 8/10 | Good, but may be seen as less elegant | |

| Backtracking (DFS) | recursion stack + path | 9/10 | ✅ Excellent, demonstrates recursion/backtracking | |

| Iterative DFS (Stack) | for stack in worst case | 7/10 | Acceptable, but more complex | |

Library (itertools.product) |

extra (but output stored) | 10/10 | ❌ May not be allowed in interviews |

Verdict: Backtracking is the safest interview choice—optimal in both time and auxiliary space, and it showcases fundamental algorithmic thinking.

6. Pro Mode Extras

Variants Section

-

Variable Mapping

What if the mapping is provided as input?

Simply replace the hardcodedphone_mapwith the given dictionary. The algorithm remains unchanged. -

Wildcard Digit

Suppose digit ‘0’ acts as a wildcard matching any letter a‑z.

Modify the mapping:phone_map['0'] = 'abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz'. Complexity increases to . -

Skip Digits with No Letters

If digits can include ‘1’ (which maps to nothing), skip it.

In recursion, ifcurrent_digit == '1', directly callbacktrack(index+1, path)without adding any letter. -

Return in Lexicographical Order

Our algorithm already yields lexicographical order because we iterate letters in alphabetical order and build left‑to‑right. -

Limit Combination Length

Only return combinations up to length k (k < n).

Modify base case: save combination whenlen(path) == korindex == len(digits). Also, possibly stop recursion early if length exceeds k. -

LeetCode 17 Follow‑ups

- 17 (original): Exactly this problem.

- Modified: Return combinations as they would appear on a phone screen (e.g., with dashes). Just format the string accordingly in the base case.

-

Multi‑transaction Version (Inspired by Stock Problems)

While not directly related, a conceptual analogue: generating all combinations is like exploring all paths in a decision tree, similar to exploring all buy/sell sequences in stock problems with constraints.

Interview Cheat Sheet

-

Clarify Upfront:

- Should empty input return

[]or[""]? (Here:[]) - Is the mapping fixed? (Yes)

- Can digits be repeated? (Yes)

- Should empty input return

-

Immediately Mention Complexity:

- Time: where is digits length.

- Space: for recursion, plus for output.

-

Start with Backtracking:

- Explain the decision tree: each digit → branch per letter.

- Write the recursive function with clear base case and backtracking step.

-

Test Thoroughly:

""→[]"2"→["a","b","c"]"23"→ 9 combinations"7"→["p","q","r","s"]"77"→ 16 combinations

-

Optimization Tips:

- Use

listforpathandjoinat the end for efficient string building. - If concerned about recursion depth, mention iterative BFS as an alternative.

- Use

-

Bonus Points:

- Discuss trade‑offs between BFS and DFS.

- Mention that constraints make even exponential solutions feasible.

- Note that the problem is a classic Cartesian product enumeration.